Continued binational cooperation in stainable Colorado River management benefits nature, communities, and farmers in the Delta region

May 18, 2022

On May 1, water began flowing into the arid Colorado River Delta for the second consecutive year, as part of an ongoing program of scheduled deliveries, to advance sustainable management of the Colorado River, and to restore this region of vital and historic importance. Formalized under a bi-national agreement and implemented through the U.S. and Mexican sections of the International Boundary and Water Commission, these transformational water deliveries are supported by an alliance of conservation organizations from the United States and Mexico.

The releases of water designed to mimic the river’s natural spring flows began on Sunday, May 1, and will extend through mid-September, delivering approximately 35,000 acre-feet (43.14 mcm) of water downstream into the long-depleted Colorado River Delta. The strategic water deliveries will be very similar to the successful 2021 program, tactically managed and designed to maximize the water’s impact. The highest flow rate is expected in early June, which will once again amplify the environmental and recreational benefits for the central delta. The water flows will continue for 20 weeks, bringing support to wildlife habitats while also being able to be enjoyed by local communities.

“Our Raise the River coalition continues to work collaboratively with the governments of the United States and Mexico to allocate scarce water resources in the most efficient manner to improve water security in the region, while also supporting the tremendous resilience of the Colorado River Delta,” said Carlos de la Parra, Academic in border studies specializing in water issues, and a member of the Minute 323 Oversight Group.

Members of the Raise the River coalition of conservation non-governmental organizations (NGOs) continue to play an active role in the implementation and monitoring of water deliveries, as specified and required under the binational agreement, Minute 323. These organizations include the National Audubon Society, The Nature Conservancy, Pronatura Noroeste, The Redford Center, Restauremos el Colorado, and Sonoran Institute, which have been working collaboratively for more than ten years to bring water and life back to the Colorado River Delta.

The continuation and implementation of the program come at a critical time for the Colorado River. In April it was designated by American Rivers as the “Most Endangered River of 2022”. This was based on the Colorado River’s significance to people and wildlife, coupled with the magnitude of the threats to the river and its neighboring communities from the combined pressures of climate change and overallocation. The collaborative restoration work by Raise the River is essential to moderate the threats that led to this designation by American Rivers.

After years of drought and declining reservoirs made worse by climate change, Colorado River water users in 2022 are experiencing unprecedented shortages, and river operators are taking unprecedented actions to preserve infrastructure viability. Conditions are expected to further deteriorate as climate change impacts become more severe over time, expanding water shortages for people and nature. The modest Minute 323 environmental flows will ensure water is available for the birds and other wildlife that depend on the Colorado River in its delta.

“The monitoring of environmental impacts has proven very helpful to inform how to obtain the greatest benefits from the smallest amounts of water delivered into restoration sites,” said Francisco Zamora, Director General of Sonoran Institute Mexico. “This information becomes increasingly relevant as we face droughts with more frequency, not only in the Colorado River basin but also in other watersheds.”

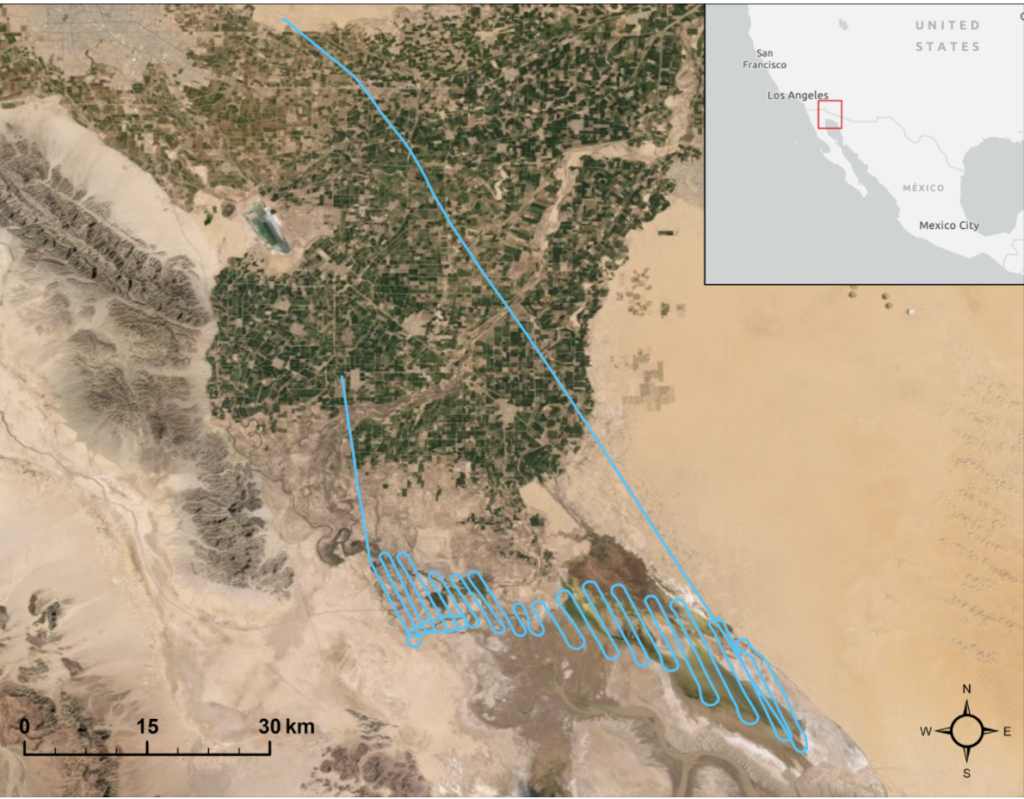

As with the 2021 program, water will be delivered to the river corridor in the central delta via existing irrigation canals in the Mexicali Valley that distribute Colorado River water to Mexicali’s farmers. The Colorado River’s water is diverted into this canal system just south of the United States – Mexico border. Once there, it flows down the canals to specific locations where the Raise the River coalition partners have developed successful restoration sites, and where these programmed releases of water can benefit the habitats and the wildlife that use them.

“Based on our prior work and the careful monitoring of its impact, we have been able to steadily increase the extent of restored sites in the delta. This expansion of healthy habitats has compounded the positive impacts on wildlife in the region,” explained Gaby Caloca, Coordinator, Water and Wetlands, Pronatura Noroeste, a Mexico-based non-profit conservation organization that manages several of the restoration sites. “These water releases are vital to support our ongoing restoration efforts,” she added.

These water releases are implemented under the terms of Minute 323, the multi-faceted binational treaty agreement negotiated between the U.S. and Mexico federal governments in September 2017. The treaty and this historic accord define how the two countries share Colorado River water through 2026 amidst growing pressures on water resources. It is part of a larger Colorado River policy framework that provides multiple benefits for water users on both sides of the border, with guidelines for sharing surpluses in times of plenty and reductions in times of drought, as well as incentives for leaving water in storage, and conserving water through joint investments in projects from water users in both countries.

“Ten years ago, the United States and Mexico modernized Colorado River management, collaborating to proportionately share surpluses and shortages in the Colorado River’s water, while boosting cross-border investment in water conservation and beginning to restore the Colorado River in its delta,” stated Jennifer Pitt, Colorado River Project Director, National Audubon Society, and Co-Chair, Raise the River Steering Committee. “Our collaborative efforts and demonstrated commitment to improving water supply for nature and people is a shining example of what two nations can achieve when we work together.”

The 143-day program of scheduled water releases is part of a broader commitment under Minute 323 to provide water for the Colorado River in its delta, for supporting key restoration sites for the conservation of riparian habitat in the river’s corridor through 2026. The sites that receive this water are a part of the international cooperative management standard established by Minute 319 (in effect from 2012 to 2017), providing proven benefits to wildlife species and communities in the Colorado River Delta region in Mexico. The United States and Mexico are providing 2/3 of the total water committed (140,000 acre-feet or 173 mcm over 9 years) and the Raise the River coalition of NGOs is providing 1/3 of the water (a total of 70,000 acre-feet or 86 mcm, over 9 years).

“Through these cooperative efforts, we are rewriting history by increasing the resilience of the Mexicali Valley,” said de la Parra. “Coming together once again, the U.S. and Mexico are allocating resources to improve the water delivery infrastructure, helping Mexicali Valley farmers increase their resilience to the impacts of climate change,”

With climate change amplifying the impacts of overuse and overallocation of the Colorado River, collaborative water management is vital to increase the resilience and sustainability of this essential resource. Raise the River is working with Mexico’s national water authority, CONAGUA, and Mexicali Valley agricultural water users to share opportunities for more efficient water use and conservation in a series of ongoing workshops. Additionally, Raise the River and its coalition members have active community engagement programs within the Mexicali Valley that offer environmental education and provide recreational opportunities in the newly restored green areas.

“Our work in the Colorado River Delta is becoming a model for long-term water-sharing agreements across borders,” says Pitt. “Since the initial releases of water for the environment in 2014, we have demonstrated the long-term benefits of binational cooperation for the environment, for the river itself, and for all water users in the region.”

Raise the River is committed to continuing its work to bring water and life back to the Colorado River Delta. Its active involvement in the 2022 program of strategic water releases is an important part of its ecosystem restoration efforts, which serve to help combat the impacts of climate change and water scarcity that are projected to intensify in the coming years. It is through the continued collaboration, cooperation, and participation of each of the various stakeholders in this region that we can raise awareness and support for the Colorado River Delta.